By Christina Vojta (research assistant) & Dara Adams

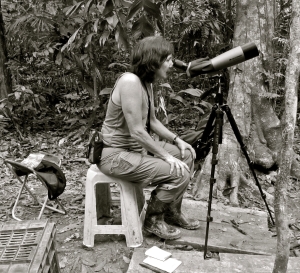

Christina observing the harpy nest through the spotting scope.

High in an ironwood tree, a pair of obsidian eyes peer watchfully from a ghost-gray face, majestically crowned with a fan of feathers. I spin the spotting scope into focus and the eyes meet mine; they lock my gaze, and I gasp. The power of the creature is palpable, even across the 100-meter distance that separates us. The bird’s plumage is striking, with dark steel gray wings and upper chest contrasting handsomely with its pure white torso. I watch transfixed as the creature slowly spreads its wings, revealing a wingspan of over two meters and a pair of hefty talons the size of butcher knives. This is the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja), the spirit of the Amazon, the monkey’s nightmare.

As the largest raptor in the Amazon rainforest, the harpy eagle is built to impale and consume monkeys and sloths, some of which weigh up to 7 kg (17 pounds). Because of this predilection for monkey meat, Dara was interested in finding out which species of monkey harpies frequently ate and whether monkeys altered their behavior or travel paths in response to eagle presence. To answer these questions, field assistants and volunteers, including myself, took turns monitoring activity at a harpy eagle nest, with each assistant spending four hours a day for several weeks to two months, yielding near-continual monitoring from March through August 2015.

Although the harpy eagle is a monster for monkeys, it is hard to not admire its beauty and grace. Through the scope, I can see an intricate pattern down the length of its tail created from alternating wavy lines of steel gray and white, and its legs are patterned in gray and white like fashionable leggings. The wing shoulders of the harpy are powerful and thick, and are held a bit out from the body, like the arms of a thick-muscled weight trainer. Females are larger than males, and weigh up to 9 kg (20 lbs).

Adult female harpy near the nest. Photo credits: left, Gordon Ulmer; right, Fiorella A. Briceño

One of the most captivating aspects of the harpy eagle is the flexibility of its neck. Like extraterrestrial ET, it can elevate the neck, then twist it more than 180 degrees and peer down over its back. Whether looking forward or back, the eagle can shift its head from side to side like a Hindu temple dancer, a motion that increases depth perception and helps pinpoint an environmental sound. Between shifting its neck and raising and lowering its crown of head feathers, the harpy eagle is able to evoke a wide range of emotions, including curiosity, calmness, agitation, attentiveness, hunger, and annoyance (usually over the many flies attracted by rotting meat in the nest).

The nest seated on top of the main fork of an ironwood tree. Photo by Aaron Pomerantz.

A creature this size needs a huge nest and an enormous tree fork to support it. The nest that we observed was approximately 2 m (6 ft) wide and 1.3 m (4 ft) deep, created by the adults through an elaborate weaving of sticks. Across the globe, most raptors use the same nest for several seasons, possibly because of the effort required to build these large structures, and often because the nest tree has the best location and shape for the purpose. Harpy eagles select nest trees with widely-spaced branches to facilitate flights into and out of the nest with their wide wingspans.

Project assistants Carly Fitzpatrick (foreground) and Dani Couceiro observe the chick as Dara takes data (background).

We spent most of our time observing the behavior of the chick that hatched in January or February. It quickly grew into a fluffy white version of its parents, with the same onyx eyes, black hooked beak, and feathered crown. There is nothing like a baby to warm our hearts, and the harpy chick was no exception. The chick was five months old when I began my month-long observation period, and I never tired of watching it learn about its body and its environment. By 6 months, it was nearly full-grown and had begun to develop adult plumage, but still had many characteristics of a chick, including a huge bundle of down that still persisted under the base of its tail. We were never sure if the chick was a male or female, but the fact that it rapidly attained a large size made us feel that it was a female. Nevertheless, in the absence of evidence, I will use the neutral pronoun.

Development of the chick over a five month period. The first picture shows the chick with all white down feathers in mid-March. The second photo was taken late May just before the chick left the nest. The last photo was taken in early August as the chick was making short flights in and around the nesting tree (note the change in plumage color and development of the crest). Photos from left to right taken by: Gordon Ulmer, Aaron Pomerantz, and Christina Vojta.

As with most animals, raptor behavior is a combination of genetically-programmed responses coupled with environmental learning. Many actions made by the harpy eagle chick made me realize the important role of learning during its youth, and I wondered if sufficient time for learning is one reason that harpy eagle chicks usually stay near the nest for 10 months or more. They are born with innate abilities to fly, hunt, eat, build nests, and rear young, but these instincts must be honed through learning and practice for several months.

The chick taking a mid-day snooze. Photo by Christina Vojta

For example, when the chick was ready to explore beyond the nest, its balance was unsteady and it rocked back and forth, learning to control its movements like any toddler. The first flights were only a meter or two, and required several minutes of contemplation and shuffling around before the wings were spread into flight. The chick learned about gravity by tearing off small sticks from the tree with its beak and watching them fall to the ground. The chick became increasingly aware of sounds in its environment, and often raised its crest with interest to the sounds of certain bird species, particularly flocks of macaws and parrots.

One day I watched the chick experimenting with different perch sizes, and it quickly learned that the really tiny branches would not hold its weight, as it flapped and struggled to stay perched on a 3-cm branch that flexed dangerously before the chick moved to a safer perch.

Even eating was partially learned. At first, the adults (mostly the female) fed the chick by tearing small pieces from a carcass in the nest and placing them in the chick’s mouth. However, once the chick began to feed from the carcass by itself, it made the error of attempting to ingest a huge chunk of meat in one piece, so that the meat was stuck halfway down its throat while still hanging out its mouth. After several minutes, the chick managed to wriggle the whole slab into its mouth, but it must have been an uncomfortable process because I never saw it do that again.

The adult female tears up a fresh kill and feeds it to the chick. Gif created by biologist Aaron Pomerantz. You can read more about harpies in Aaron’s article in The Huffington Post here.

Our total observation time of approx. 400 hours yielded abundant information about the importance of monkeys in raising a harpy eagle chick. Coupled with results of a previous local study of harpy eagle diet, the most frequent food items were sloths, howler monkeys, and brown capuchins, but squirrel monkeys were also significant prey along with an occasional macaw. Saddleback tamarins were present in the study area, but to our knowledge, they were never part of the harpy eagle diet, perhaps because they tend to stay in the lower canopy, move quickly, and are quite small-bodied (offering little meat).

Adult female bringing a howler monkey back to the nest. Photo by biologist Chris A. Johns. Check out more of Chris’ amazing photography here.

As the chick moved into its 6th month, the adult eagles brought fresh food less often. One day I watched the chick pluck fur from the tail of a squirrel monkey and eat the meager tail meat, and I wondered whether an adult would eventually appear with food. The chick was not able to hunt on its own but it could fly to adjacent trees, and we often could not find it for hours when it was perched silently. However, there were other days when the chick seemed to need fresh provisions, as evidenced through incessant begging cries. On my last evening watching the chick, it crouched into the begging pose of a nestling, squatting in the nest with wings held out, beak pointed skyward, emitting plaintive begging cries until dusk. I returned the next day, but there was still no fresh food. I knew that the female eventually would arrive, perhaps with another sloth, but in a month or two, our chick would need to learn to hunt by itself. And when it did, the monkeys of Tambopata would serve to carry the chick into adulthood, and perhaps into the realm of raising its own chick someday.

To learn more about our study subjects and see amazing harpy footage, check out the video below filmed and created by biologist Aaron Pomerantz and wildlife photographer Jeff Cremer.